At CES two weeks ago, I coupled my time wandering the exhibition floor with sitting in on several panels. They were all, as you might guess, about AI.

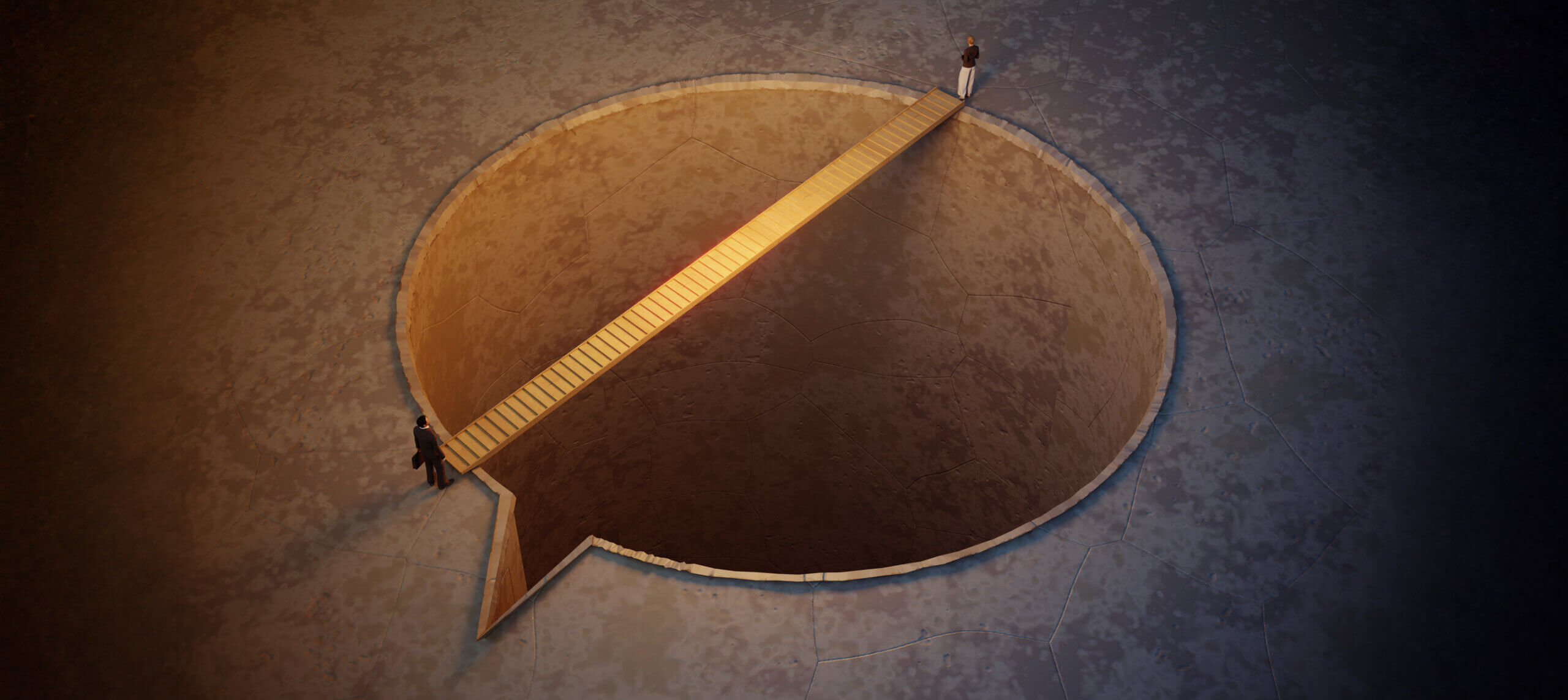

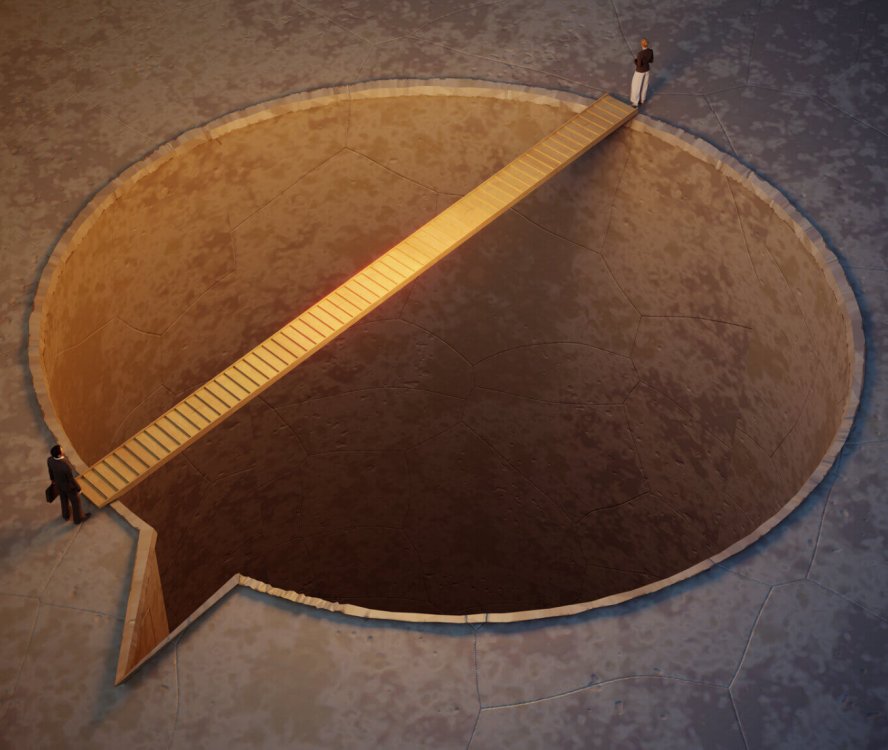

The speakers were smart. Most of the arguments were reasonable. But as these sessions went on, I noticed something striking: the panelists were not having the same conversation. There is, very plainly, a split in how we talk about AI.

The differences between panelists weren’t about optimism versus skepticism, or hype versus realism. The differences were in the language they used.

On one side, there was what I’ll call the “Silicon Valley philosophical style.” It’s abstract. It’s speculative. It speaks in future-tense.

Last year on his blog Sam Altman wrote that “in 2025, we may see the first AI agents ‘join the workforce’ and materially change the output of companies.” Dario Amodei, similarly, argues in an essay that once “powerful AI” arrives, we could compress “50–100 years” of progress in biology and medicine into “5–10 years.”

The emphasis is on trajectory and inevitability. Claims are sweeping. Timelines are compressed. The present is treated as a temporary inconvenience. In short, the Silicon Valley philosophical style asks and attempts to answer big questions about what could be true if the world would just hurry up and cooperate.

On the other side, there is the legacy enterprise style. AI is discussed largely in the present or near-present tense. We are piloting. We are evaluating use cases. We are standing up governance. We are assessing risk. Sentences are careful. The scope is bounded.

At first glance, this can look like a simple stylistic disagreement. I used to think this difference was mostly aesthetic. A vibes problem. Now, I think these are not stylistic preferences. They are coping strategies for risk.

This makes sense when you think about how Silicon Valley operates. In Silicon Valley, ideas move fast because consequences tend to move slowly. Consequences are deferred and externalized because venture capital explicitly spreads risk across the portfolio. Most startups fail and that failure is priced into the model. When the cost of being wrong is deferred or externalized, abstract thinking becomes affordable. As a result, one can make sweeping claims about how the world will work without immediately having to make them work. In that environment, philosophy is cheap. Failure is absorbed by the portfolio, rather than the speaker of the claim. Failure isn’t just tolerated, it’s expected.

Enterprises, by contrast, speak blandly about AI for a very practical reason: blandness is safer than precision.

The language of CEOs is cautious. It’s procedural. I sometimes wonder if it’s deliberately unremarkable because every word is assumed to be a contract with the future between enterprise leadership and shareholders. Every commitment has a cost. Every cost has an owner. Every owner has a performance review. Obligations create exposure and exposure, in a regulated and public organization is expensive in ways that do not conveniently reset after a funding round.

The result is a mutual dismissal. Each side is convinced the other fundamentally does not get it.

Silicon Valley appears intellectually ahead but operationally naïve to enterprises. Enterprises appear operationally mature but intellectually constrained to Silicon Valley. When the message is too philosophical, enterprises dismiss it as unrealistic. When the message is too cautious, Silicon Valley dismisses it as late. Both reactions are understandable. Both miss the deeper truth.

There is a generational component here. Many Silicon Valley actors are young – several sources cite the median age of Y Combinator founders as 24 – and in their lived experience, the world has changed very quickly. Why wouldn’t they expect the future to arrive quickly?

However, and more importantly, consequences in Silicon Valley are largely externalized. Silicon Valley can afford philosophical thinking because the system was built for failure. Venture capital firms absorb the downside. Founders are rewarded primarily for option creation, not for long-term system durability.

Enterprises cannot afford this posture. For the enterprise, failure is expensive and public. It carries legal, reputational, and organizational consequences that do not conveniently expire after a funding round.

In short, Silicon Valley optimizes for velocity of ideas. Legacy enterprises optimize for system stability.

Neither approach is wrong. But they are profoundly misaligned and neither side truly understands the other. Silicon Valley often assumes it can simply replace legacy players, underestimating the complexity and resilience of the systems they’ve built. Enterprises, meanwhile, often assume innovation can be safely imported without changing the underlying behaviors or incentives that produced it.

From this, I’ve drawn two conclusions.

First, Silicon Valley is early. Early in imagination (which is genuinely valuable) but also early in responsibility. The people doing the imagining do not bear consequences in the way institutions eventually must.

Second, enterprises want innovation outcomes without innovation behavior. They want the benefits of experimentation without the exposure to risk. They ask for transformation while preserving incentive structures that only reward short termism.

Why does this misalignment actually matter? For starters, it matters for the enterprise because it results in pilot purgatory. Promising technologies are forced to justify themselves with mature-business standards before the organization has built the capabilities required to realize the value. Ambitious visions leave Silicon Valley unshaped by the environments they must eventually inhabit so they break on first contact with constraints.

The misalignment produces wasted cycles, stalled adoption, duplicated effort, and a growing vendor graveyard on the enterprise side. Plus, it produces overconfident narratives and underbuilt pathways to deployment on the Silicon Valley side. The result is systemic friction that slows progress and breeds mutual distrust.

The problem is not that Silicon Valley and enterprises serve different functions. They should. The problem is that the handoff between imagination and durability is broken. Without translation, enterprises underinvest in genuinely transformative capabilities, while Silicon Valley overproduces futures that cannot survive contact with reality.

So what would it look like to actually bridge this gap? Not by splitting the difference, and not by asking either side to abandon what they are good at.

Silicon Valley is doing what it is structurally designed to do. Its role is valuable precisely because it is unconstrained by durability, regulation, and institutional continuity.

The burden lies with enterprise. It requires changing how risk, time, and accountability are organized so that imaginative work can exist without immediately collapsing under operational pressure. An enterprise response to this problem has to be structural.

- Enterprises need capital pools that are explicitly protected from quarterly earnings pressure and short‑term ROI expectations. These efforts must be treated as capability investments rather than product bets, with the explicit understanding that their primary return is organizational learning, not near‑term revenue.

- Progress on those initiatives has to be evaluated differently. Early success should be measured by capability accumulation (what the organization can now do that it could not do before) rather than margins. Applying mature‑business metrics too early guarantees premature shutdown.

- Long‑horizon programs must be designed to survive executive turnover. Governance needs to lock in multi‑year commitment, with funding and mandate decoupled from individual leaders. If a program disappears with the next reorg, it was never strategic in the first place.

- Finally, enterprises have to accept early inefficiency as a feature, not a failure. Early phases will look wasteful by mature‑business standards. That’s part of the process.

Ultimately, enterprises have to decide whether they want access to frontier innovation badly enough to change how they receive it. That means building the missing middle layer; the structures, timelines, and incentives that allow speculative ideas to be metabolized into durable systems without killing them or distorting them beyond recognition.

When that layer exists, Silicon Valley does not need to slow down, and enterprises do not need to pretend they are startups. Each side can remain good at what it does best. The gap between imagination and durability stops being a failure point and starts becoming a functional interface.